This series of posts accompanies a talk I give about unit testing with the xUnit test framework. Any reader who saw my talk can use this as a reference, others can use this as a starting point to write even better maintainable and reliable code. In my talk, I highlight patterns that work well with easily testable code and combine it all into a working application. All code from these articles can be found in a repository on my GitHub account.

After the first green test, I want to expand to data driven tests. These tests promote reusability by combining multiple scenarios into one generic test. To end, I'll categorize tests with metadata.

First a word about code coverage

The way I wrote this code is a bit different from how traditional TDD works. As described in the previous chapter, I wouldn't write a line of code before there is a test. I find that very convenient when I have a clear direction. The danger is that starting to write without a clear goal can lead you into a swamp. Recognizing and backing out of a swamp can be a lot of work. Sometimes I think how I want to structure my code and then implement that code. As a last step, I write all the tests for that bit of code.

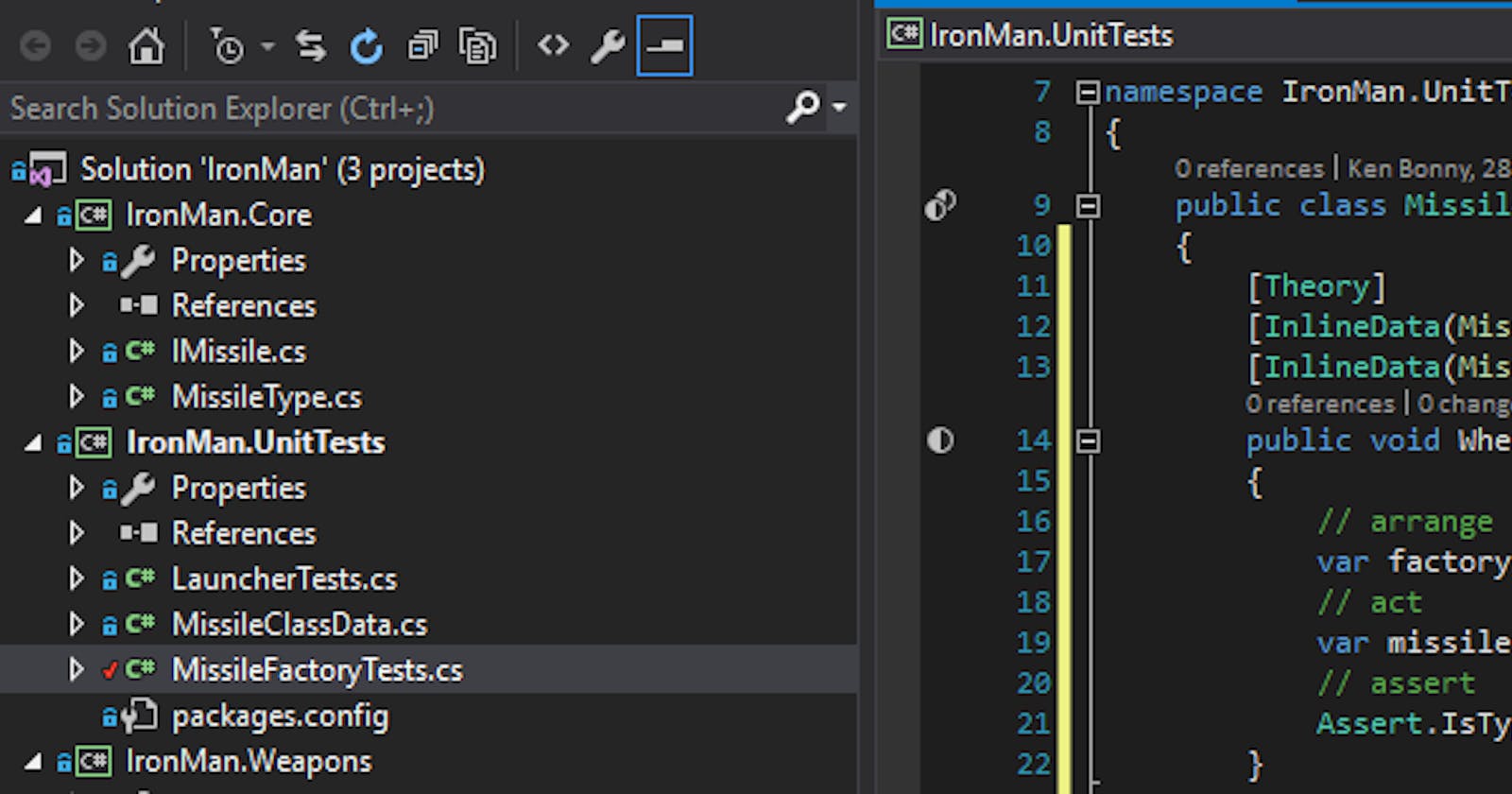

The set up

I have already prepared a bit of code: two IMissile implementations (LaserGuidedMissile and HeatSeekingMissile), a MissileFactory and an enumeration MissileType (Guided and Autonomous). The missiles are empty classes and the factory returns an implementation based on the provided missile type. I'll let you figure out which type returns which missile.

Besides the code for the MissileFactory, I also wrote some test to verify that it works as intended.

[Fact]

public void When_building_guided_missile_then_expect_LaserGuidedMissile()

{

// arrange

var factory = new MissileFactory();

// act

var missile = factory.Build(MissileType.Guided);

// assert

Assert.IsType<LaserGuidedMissile>(missile);

}

[Fact]

public void When_building_autonomous_missile_then_expect_HeatSeekingMissile()

{

// arrange

var factory = new MissileFactory();

// act

var missile = factory.Build(MissileType.Autonomous);

// assert

Assert.IsType<HeatSeekingMissile>;(missile);

}

These two tests look very similar. I'd even go as far as to say that there are only two differences: the missile type and the asserted type.

Lucky for me, I can combine the two tests into one and feed the data into the test in a number of ways. The easiest is the InlineData attribute, another is via MemberData and the last one is via the ClassData. I'll explain each one below.

The InlineData attribute

xUnit supports a way to reuse tests, just like I would reuse code. By replacing the [Fact] attribute with the [Theory] attibute, the test becomes a data driven test which accepts parameters. The data has to come from somewhere. The easiest way is to put at least one [InlineData] attribute below the [Theory] attribute and specify the input data in the same order as the test expects them.

To make the naming convention of When_then_ still work, I use the type name instead of the expected value. So this test would be named _When_building_MissileType_then_expect_Type_. Again, describe what is being tested, experiment with naming conventions.

The rest of the test is largely the same. The arrange creates the factory, the act builds the missile and the assert checks the type against the built missiles type. The only difference here is that I cannot use the generic IsType<> method, I replace it with the non-generic IsType(type, object) overload.

In the end, the code looks as follows:

[Theory]

[InlineData(MissileType.Guided, typeof(LaserGuidedMissile))]

[InlineData(MissileType.Autonomous, typeof(HeatSeekingMissile))]

public void When_building_MissileType_then_expect_Type(MissileType missileType, Type expected)

{

// arrange

var factory = new MissileFactory();

// act

var missile = factory.Build(missileType);

// assert

Assert.IsType(expected, missile);

}

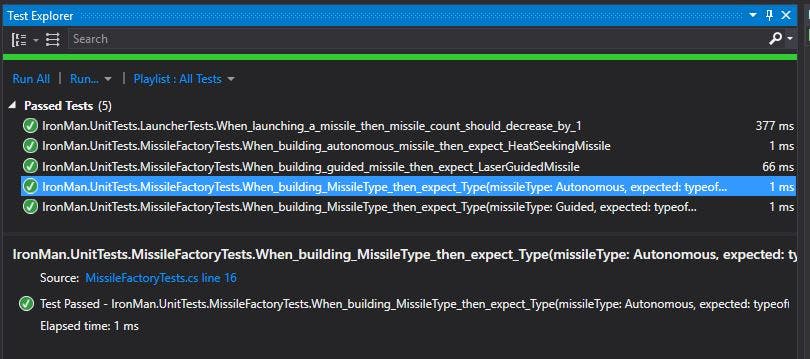

Such code could have saved me a lot of time in the past. When I run this test, the Test Explorer shows two different tests like this:

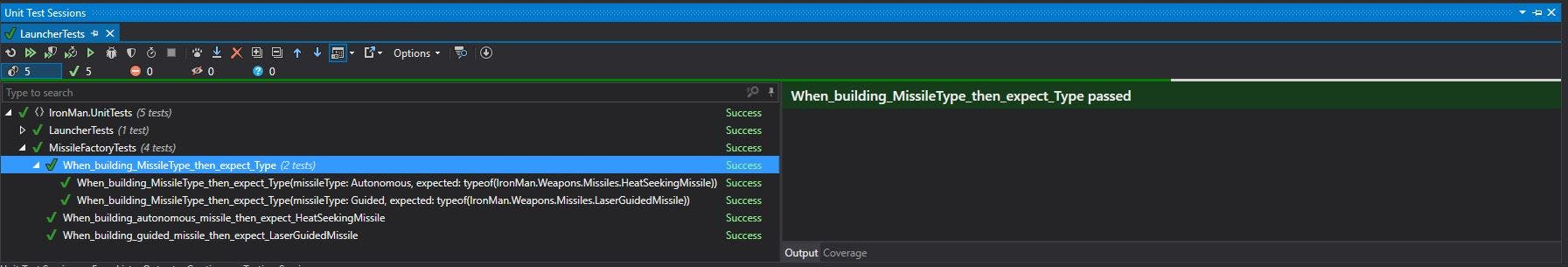

The ReSharper test runner shows it more clearly, in my opinion, by showing the test and the instances:

So each test got its own line to represent a succeeded or failed run. Which keeps the test overview clean and readable.

The MemberData attribute

The [InlineData] attribute can only pass simple objects to the theory. If I want to test with more complex data, for example a missile object, or data from external sources such as a file or database, then I must use the [MemberData] or [ClassData] (see next chapter) attributes.

When I add the [MemberData] attribute, I have to specify the name of a public static property or field that implements the IEnumerable<object[]> interface. The easiest way is to just add a field with that signature and choose an appropriate name. The field can then be instantiated inline or in the constructor.

The result in the test explorers will be the same as that from the [InlineData] attribute.

I've added a test to the Launcher class that works with actual missiles.

public static readonly IEnumerable<object[]>

{

new object[] {new HeatSeekingMissile()},

new object[] {new LaserGuidedMissile()}

};

[Theory]

[MemberData(nameof(MissileData))]

public void When_launching_specific_Missile_then_missile_count_should_decrease_by_1(IMissile missile)

{

// assert

var launcher = new Launcher(new List<IMissile>; { missile });

// act

launcher.Launch();

// assert

Assert.Empty(launcher.Missiles);

}

Side note: this would be a component test because I'm using the implementation of the missiles in my tests. The field doesn't need to be readonly, but it's again a little optimization since this won't be able to change during test execution.

The ClassData attribute

The last data attribute that is available is the [ClassData] attribute. This attribute accepts a type that implements the IEnumerble<object[]> interface to be accessible by the theories using the data. This is mainly used when loading data for specific tests contains a lot of work and I would want to split this off into another class to hide the complexity.

The first thing I do is make another theory test and put the [ClassData] attribute between the [Theory] attribute and the method signature. I specify that the type of the class will be the MissileClassData class.

Now I create a new class and call it MissileClassData. It will inherit the IEnumerable<object[]> and that will add two methods, both getting an enumerator. If I would want to create a specific enumerator without returning the enumerator of an already existing class such as a List<T>, then I would read a beginners tutorial.

[Theory]

[ClassData(typeof(MissileClassData))]

public void When_launching_missile_from_classdata_then_decrease_missile_count_by_1(IMissile missile)

{

// arrange

var launcher = new Launcher(new List<IMissile>; {missile});

// act

launcher.Launch();

// assert

Assert.Equal(0, launcher.MissileCount);

}

public class MissileClassData : IEnumerable<object[]>;

{

public IEnumerator<object[]>; GetEnumerator()

{

// get data from database or webservice

// or do some complicated computation

yield return new object[] {new HeatSeekingMissile()};

yield return new object[] {new LaserGuidedMissile()};

}

IEnumerator IEnumerable.GetEnumerator()

{

return GetEnumerator();

}

}

This is the most basic example I go into. If I want to fetch data from a database, I could do so in the constructor and then load that data into a private field. This class will be instantiated once for each theory test it calls. This means that _When_launching_missile_from_classdata_then_decrease_missile_count_by_1_ creates an instance of the MissileClassData class and then runs over all the items in the enumeration. If the MissileClassData class is used for multiple tests, then it would instantiate a new MissileData() for each test, in this case test fixtures become interesting (see next blog post).

Again the result in the test explorers will be the same as that from the [InlineData] attribute.

Grouping tests

The last two tests are actually component tests, because they test more than just the class they are meant to test. They use actual implementations of the IMissile interface. Thus I should indicate that they belong to another type of test.

With the [Trait] attribute, I can add metadata to tests. The first parameter is the key of the metadata, the second parameter is the value that goes with the key. This can be a bit confusing when starting to work with the xUnit framework. I like to think about traits as a sort of claim from claims-based authentication.

To group tests, the easiest way is to set the key to "Category" and then specify the name of the category in the value part. In this case "ComponentTest". Both the Visual Studio Test Explorer and ReSharper Unit Test Sessions understand the "Category" key and allow sorting on that trait.

[Fact]

[Trait("Category", "ComponentTest")]

public void When_launching_missile_from_classdata_then_decrease_missile_count_by_1(IMissile missile)

{...}

The benefit is that you can add more information about the tests. I could, for example, add a trait with a key "Author" and a value of "KenBonny" to show that I created that test. Traits could also be useful to have a "TestIdentifier" key and each value can have the identifier of a test from documentation. This flexible system allows for a lot of possibilities to add additional data to tests.

There is a way to create custom traits, but it is a bit more complex and I'll leave that up for experimentation.

Conclusion

By replacing the [Fact] with a [Theory] attribute and adding either a [MemberData], [ClassData] or multiple [InlineData] attributes, I can reuse tests with the same logic but different data.

With a [Trait] theory I'm able to provide additional data to a test. Most notable is the "Category" key which can group tests in different categories, devided by the value that is supplied.

Next, I will discuss further code reduction by using test initialization and cleanup. If anybody notices any inconsistenties, please contact me on twitter or via email.